Harbinger Magazine is glad to be interviewing Ezra Lesser. Ezra has arranged and produced “Cosmic Energy” for the Harbinger Orchestra project. You can find this music on the Harbinger Orchestra Album on the Dave Bixby Bandcamp website.

Ezra, thank you for granting us this interview. To start with, where were you born and where are you living today?

Thank you for kindly inviting me for this interview. I was born in a rural area of southeast Michigan, United States, which is where I grew up and went to school. I moved to the San Francisco Bay area of California in my early 20s and stayed there for a few years while going to school, before graduating and moving to eastern France. That is where I live now, near the border with Geneva, Switzerland.

Would you tell us about your occupation and living in France?

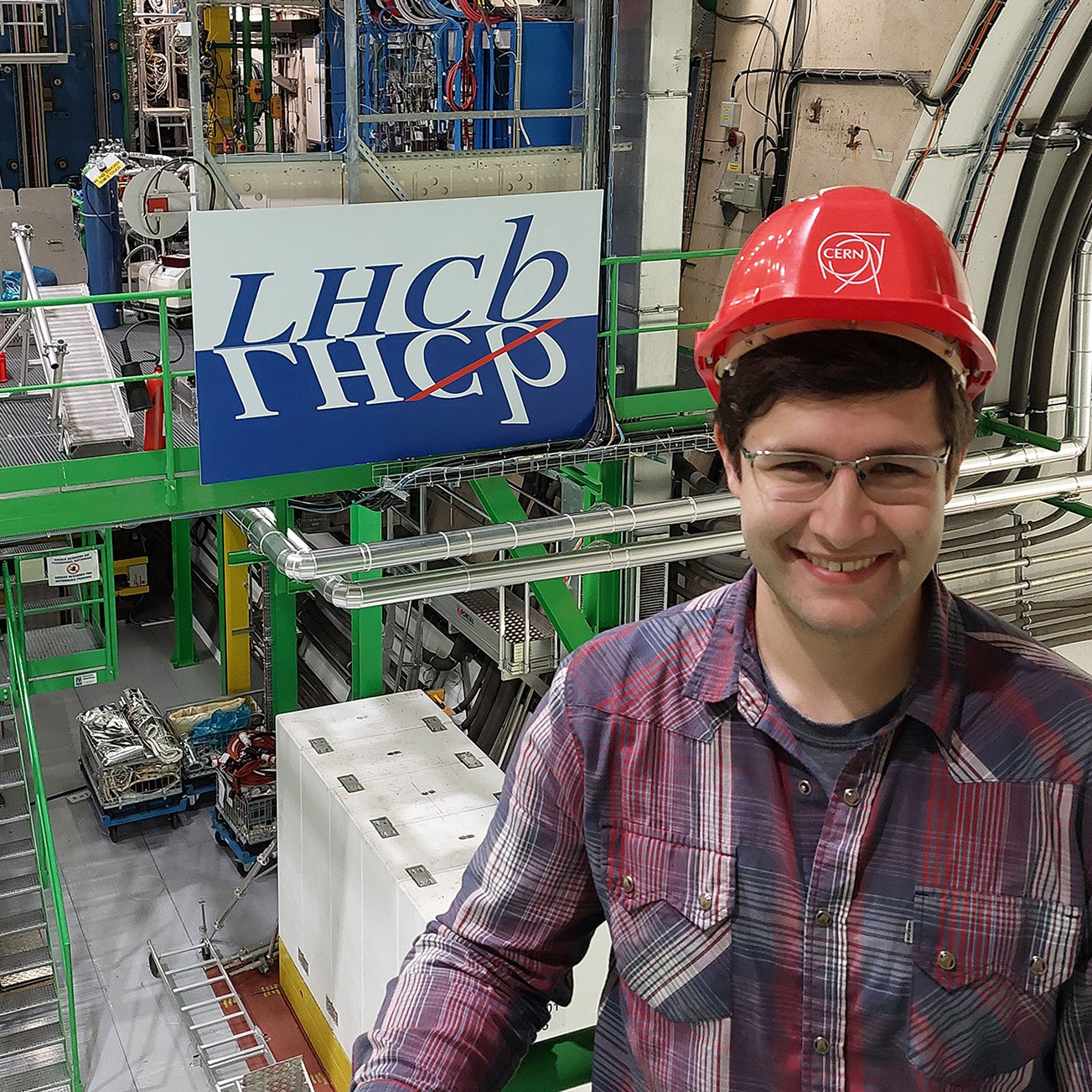

I am a research fellow at CERN, a place in Europe where scientists explore the tiniest building blocks of the universe. I study a fundamental force of nature that holds everything together, like glue at the center of every atom. When we heat matter to extremely high temperatures, the particles inside—protons and neutrons—melt into something like a primordial fluid, called quark-gluon plasma. At CERN, tiny droplets of this plasma have been made for the first time since the universe was created, allowing us to better understand the birth of existence. For me, underlying this science are deep philosophical questions that humanity has pondered for millennia: Who are we? Where do we come from? Why do we exist? In many ways, physics is the study of God.

We know that you remaster vinyl records. When did you start doing this?

I recall playing some records at a relative’s house in early childhood, but I only started collecting my own when I was 10 or 11, after finding a stack of albums at a local church giveaway. Not having a record player, I fashioned my own using a thumb tack, a paper horn, and a pencil for the spindle, which worked just about as well as you’d expect. However, my parents observed my enthusiasm, and gave me the awesome gift of a vintage turntable for my next birthday, along with a stack of used LPs. I was hooked, and from then on, I was always spinning a record in my room.

I started collecting more seriously in high school, because it was the cheapest way for me to acquire recorded music. I could buy vinyl records 10-for-a-dollar at the local Salvation Army, while it would cost 99¢ to download a single low-quality song on iTunes. So I started visiting resale stores regularly and buying classic rock and folk albums by the dozen, taking home anything that looked remotely interesting. I discovered a lot of music this way, including many things that had never been reissued on any other format. The albums I was buying weren’t on CD, nor iTunes. If I wanted to listen to those albums while I was in the car, or at school, or at a friend’s place, I had to make a recording from the original record.

Making these recordings, I discovered that there was a vast community of enthusiasts making digital transfers of their records and sharing them online. I realized very quickly that my recordings were not up to snuff, and slowly started saving my money to upgrade my equipment every year. I learned a lot from listening to other people’s recordings, and still having young ears, I was able to easily tell between what sounded great, and what didn’t. After a while I also started building and modifying equipment myself, to better suit my recording needs and to reduce background noise in my transfers.

Would you tell us a little bit about how you do your remastering work?

Sure. There are generally two phases of creating a tape-like digital master from vinyl: capturing a clean high-resolution transfer, and performing manual restoration. First I select a disc to work with; rarely do I use anything in less than perfect shape, which makes the later restoration work much easier. I carefully clean and center the disc on my turntable, checking its position down to fraction of a millimeter before clamping it down. Then I record the disc, using equipment assembled with minimal clutter in the signal chain.

After obtaining an acceptable transfer, I begin manually restoring the audio. This includes removing any clicks, pops, or unwanted distortion by hand. Manual restoration is the only way to completely preserve the natural sibilants in music—the snap of a snare, fuzz on a ‘60s guitar, or light acoustic strumming—while removing the noise that makes vinyl sound like vinyl. However, it is extremely time-consuming, usually taking 1 to 2 hours per minute of audio. And sometimes creativity is required when there are more challenging issues.

Have you written and recorded any of your original music?

Yes, I am also a musician. I started writing and transcribing music when I was in middle school. I would create scores for myself and my schoolmates, and occasionally we got the chance to play them. Sometimes I would stay up till 2:00 in the morning writing or recording things on different instruments, then layering them together to see what it sounded like. There was a lot of Frank Zappa spinning in my room around that time, which inspired me to create non-traditional, experimental songs.

Many of my teenage hours were spent transcribing recordings into written form. When I was in high school, I was contacted by a professor in northern California who had found my transcription of Zappa’s “Echidna’s Arf” and wanted to play it with his jazz ensemble. I was elated, and some months later he sent me a video of the group playing my arrangement, which was mind-blowing. I was a kid from rural Michigan, and some college on the other side of the country was playing the score I transcribed. Later on, I started focusing more on the engineering side, which I find very fulfilling. But I still play, record, and transcribe when the inspiration strikes.

What instruments do you play and record with?

I started playing piano when I was young. My parents supported my interests by giving me weekly piano lessons, which is where I learned to read music. I started playing clarinet in middle school, then branched out in high school to other woodwinds, mainly tenor saxophone, alto saxophone, and bassoon. My high school band director allowed me to borrow these many instruments to learn. I had the opportunity to play in seven school jazz bands at that time, playing piano, woodwinds, and upright bass. My parents also bought me an electric guitar—a Fender Squire Strat—and a tiny ‘Rocktron’ amp with a distortion button. I played some guitar, but didn’t understand the theory until later on in high school, which is when I became more interested in the instrument. Nowadays I mainly play guitar and alto saxophone, but I have also dabbled with banjo and sitar, the latter of which is an extremely beautiful yet challenging instrument from a completely different musical world.

When and how did you discover the Ode to Quetzalcoatl LP?

I think it was 2011 or 2012. I had developed an interest in “psychedelic” music, which I found to be much more creative than the popular music that I had heard on the radio growing up. For example, listening to “Ego Trip” by Ultimate Spinach or “Incense And Peppermints” by Strawberry Alarm Clock, the chord progressions are somehow familiar, yet simultaneously twisted: chords that you expect are switched out for others, in a way which doesn’t make sense from a traditional theory perspective, but totally works. Think about the Stravinsky-esque opening chords of Hendrix’s “Purple Haze”: I was fascinated by this. Jazz made sense to me, and I could follow the many ii-V-I iterations of “Giant Steps,” but the best psychedelic rock music of the 1960s exhibited uncharted freedom and innovation.

As I started exploring psychedelic music, I somehow stumbled upon Klemen Breznikar’s interview of David Bixby. Being a Michigan native, I was fascinated by the story, and acquired a copy of the Guerssen reissue. While it became obvious that the music was not “psychedelic” at all, the realness of the entire ‘era’ suddenly hit me. There are few recordings on this planet as earnest and honest as “Drug Song.” The Quetzalcoatl album, for me, embolizes a darker side of the 1960s: psychological distress, religious cults, and eventually, redemption. It’s hard for me to imagine a better representative of damaged acid-folk than Ode to Quetzalcoatl; it’s simply the best album in its style.

Why did you choose “Cosmic Energy” to record?

I discovered the Harbinger album years after Quetzalcoatl, and I honestly like it even more. The opener “Cosmic Energy” has awesome imagery to play with: “cosmic energy is coming right to me…” – Physicists are now trying to understand the nature of cosmic dark energy, which is about three-quarters of the energy in our universe, but we know almost nothing about it. The universe is expanding, and its expansion is accelerating, but humanity has no understanding why. It’s one of the greatest mysteries in physics. “Cosmic Energy” (the song) captures that same feeling of mystery and wonder, and I tried to reproduce it in my version. I rewrote the second half of the song entirely, including some relevant quotations from various physicists: Saul Perlmutter (Berkeley), Steve Allen (Stanford), and others, but you’ll have to listen closely to hear them. About 95% of that song was recorded in and around my old apartment in Berkeley, with finishing touches put on after I moved to France. All instruments and sounds are played/created by me. I wanted it to be fully original, without reusing any external sounds or effects.

Who is your favorite artist and band?

That’s a tough question for any music fan to answer! I still appreciate Frank Zappa, especially Joe’s Garage, which is an inspirational and conceptual masterpiece. My dad turned me on to Frank and to that album specifically when I was a teenager, and it totally changed what music meant to me. As for bands, Pink Floyd or the 13th Floor Elevators are probably my favorites. The Dark Side of the Moon, of course, is one of the greatest albums ever recorded. Actually, it may have been delivered to Earth by some higher lifeforce altogether. Easter Everywhere, which was recorded 6 years earlier, is a piece of art arguably even more amazingly-conceived, with “Slip Inside This House” in particular a life-guiding triumph. I also like Love Forever Changes, The Beach Boys: Pet Sounds, Relatively Clean Rivers, Anonymous: Inside The Shadow, Zerfas, Flower Travellin’ Band: Satori, Neil Young, the United States of America, the Doors, Captain Beefheart & His Magic Band, the Perth County Conspiracy, and dozens of similar artists.

Is there anything you would like to say to our readers?

If physics be the study of God, then music is the study of man. I think what is great about the Quetzalcoatl album, like so many great pieces of art, is not only its real authenticity, but its basal undertones of searching for something. That reflects on us as listeners, as we try to understand our own existence within the context of the music. Art offers a mirror which can transcend time and alter the lives of people who were not even born at the time of its creation. It’s impossible to predict how the art of today will affect tomorrow. But it’s clear that the impact of the Quetzalcoatl album, and for that matter the Harbinger album, too, has only begun to resonate through the ages. May we reflect wisely.

– David Anthony